Hello.

The idea for the text arose a long time ago, but in the list of planned articles the turn to write it has only now reached. In some ways, this is symbolic: at the end of the year, reflect on how things really are, and think about “what would happen if,” hoping for a different development of events next year. It is unlikely, of course, that anything will change globally, but even more so, one can freely express assumptions. The initial trigger for raising this topic was found in a discussion in the comments to Eldar’s article about the impact of US sanctions on business. More details about the arguments can be found at the link below:

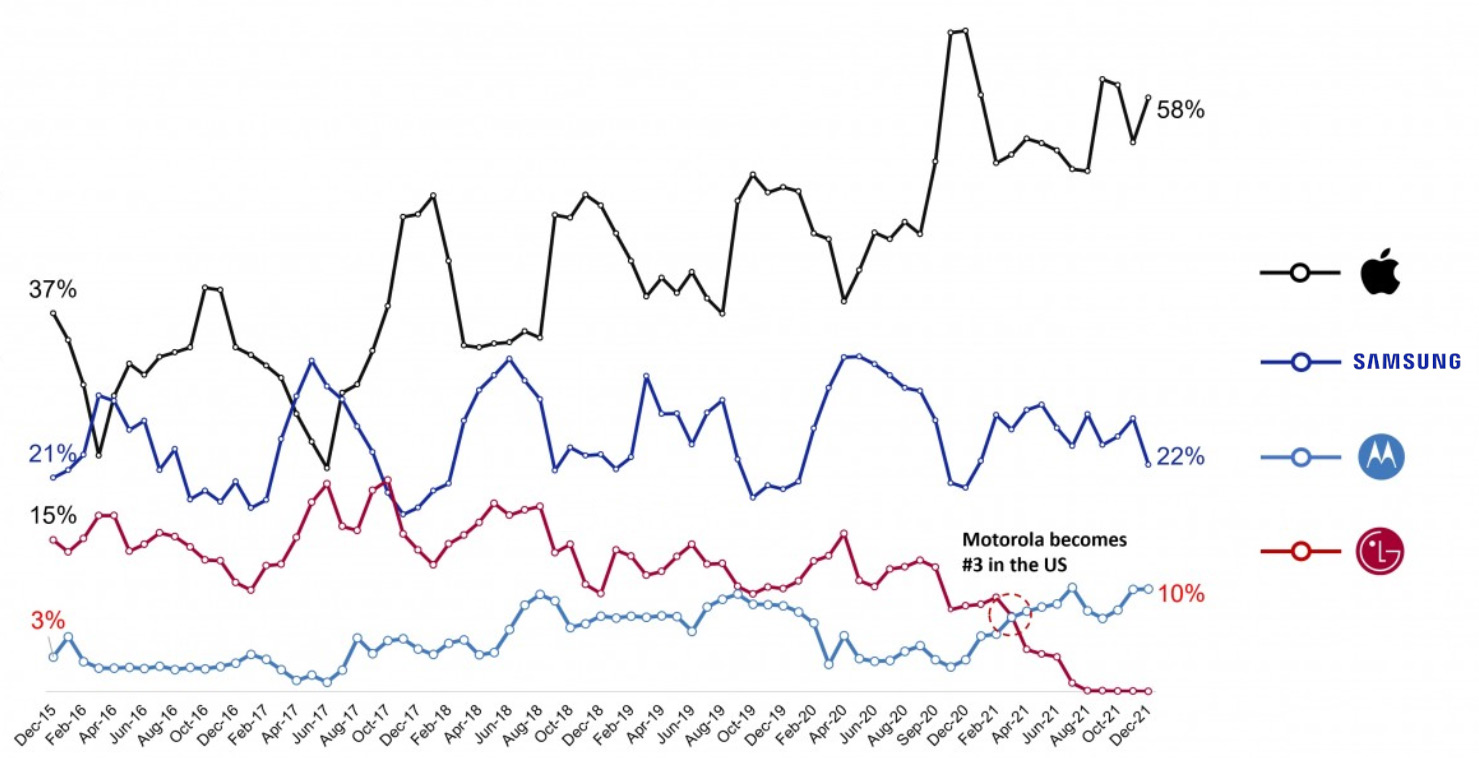

The material is interesting. I like how the presentation of dry facts turns a beautiful, elegant mantra about the technological superiority of the United States into a pumpkin, the seeds of which are packaged by organizations and specialists from Europe, and grown by producers from China. But today I would like to talk about addiction. It’s about what drives companies. Dear Andrey Ustinov expressed the opinion in the comments that the market is inextricably linked with money and any changes in it can be dictated solely by material gain. Only the planning horizon will differ. Everything is logical. Within the framework of the tactics of various companies, one can easily trace their intentions, which, one way or another, are aimed at capturing shares, occupying niches, squeezing out competitors, etc. And each of these events will ultimately enrich the one who will be its initiator or final beneficiary. For example, we all love smartphones. See how the situation developed for Nokia:

It is clear to the naked eye to whose advantage the fall of the Finnish manufacturer in North America was. Or a similar story with Motorola. Despite the fact that the company was pretty much gutted by Google, the manufacturer managed to briefly take its place due to the departure of LG:

This all means that the situation demonstrates a clear pattern in the functioning of the market. If they don’t buy the flagship of one manufacturer, they will buy the flagship of another. The symmetry of jumps in sales of Apple and Samsung in the graph above confirms this. And at first glance, one gets the impression that, having a fixed money supply, for example, for the annual update of a flagship, each citizen, when purchasing a device from a particular manufacturer, will contribute to this schedule. Everything would be perfectly simple. But we can often see a mess in such statistics. For example, a decrease in the number of devices sold, but at the same time an increase in income. This is most often associated with a banal increase in prices, but despite such actions of the manufacturer, people continue to buy the product. And upon careful study of the picture, additional arguments emerge. I usually bring two of them. The first is psychological inertia. The user is used to it and does not want to give up something familiar in favor of new products. Secondly, the product is so superior to its competitors in the implemented functions that the overpayment seems justified. And it always makes me think. After all, if you make a product that, for a specific user, is superior to a competitor in terms of the presence of new functions, then you can get a buyer by satisfying their needs in advance. That is, without raising prices, to win people over to your brand as one that cares about users. But indications of such actions were regarded by my opponent as long-term planning, and not goal-setting other than profit, since ultimately the manufacturer who made such a decision will receive a loyal client from whom it will be possible to make an honest profit, but later. And again, everything speaks in favor of the fact that material wealth is the only driving force for the manufacturer. But something in this conclusion haunted me, and I, having briefly outlined the essence of the dispute in the comments to the outline of the article, left the idea to ripen. And when I got to her yesterday, everything somehow fell into place by itself. At least for me.

But first, let’s establish some framework for the perception of familiar terms. In discussion with Andrey we used the words “planning” and “goal setting.” And, in general, the terms are correct.

Planning is the allocation of resources to achieve set goals.

Sounds simple enough. Moreover, the process is familiar to many of us as accounting for future expenses for some time. Its main advantage is its specificity, since in order to account for future expenses, we most often have comprehensive information about all possible factors that can influence these expenses. Now let’s take a look at the term “goal setting.”

Goal setting is the primary phase of management, which involves setting a general goal and a set of goals in accordance with the purpose of the system, strategic guidelines and the nature of the tasks being solved.

And here we already understand that the “general goal”, “purpose of the system” and “strategic guidelines” are something that lies far beyond the planning time frame. The mere fact that we are talking about a set of goals suggests that there is no talk of any clear planning. And if we take into account the fact that in our world everything is interconnected and events can mutually influence each other almost in accordance with butterfly effectthen expenses within that same aggregate will be reviewed and adjusted at the slightest change in the situation.

But let’s return to smartphones. They have been actively developing over the last 15 years. And what have we managed to see during this time? The rise and fall of Nokia, LG and HTC, the rise of the iPhone, the pursuit of Samsung, the emergence and disappearance of Chinese companies with separate stories in the form of Xiaomi and Huawei. And all this in 15 years. Andrey pointed out in the comments the connection between the crisis we are facing today, observing US decisions to impose restrictions, and capitalist cycles. And why Apple, under Jobs, organically integrated, albeit alien, new ideas into its products, and under Cook, it exclusively optimizes everything that is possible, he explains this way:

To dot all the i’s, a little education. The Internet told me that the following stages are usually distinguished in capitalist cycles: crisis, depression, recovery and recovery. At the apogee of the rise, overproduction logically arises, which triggers the crisis. Cycle. And it is stupid to deny this pattern, since we have been observing it literally for many decades in a row. What is confusing in this “working” scheme is the statement that when the cycle closes and the transition from the last phase to the first, the consequences in fact become causes. If we think in analogies, then Novikov’s principle of self-consistency, which explains the paradoxes of time travel, is closest to such a loop. In simple words, the point is that by going into the past, you become the cause of the development of events that will lead you to the moment when you go into the past. Or, if according to the textbook:

“…when moving into the past, the probability of an action that changes an event that has already happened to the traveler will be close to zero.”

There are many decades in a row mentioned above for a reason. If you believe the sources, then similar cycles with crises of overproduction have been recorded since 1825. The duration of crises varies, as does their severity, impact on society, production and the market, but the fact that they are repeated indicates that the usual development of events within the framework of the capitalist cycle stably leads to a crisis. And if we look at the definition of capitalism, which is the cause of crises, we will see that the basis for decision-making within a given economic system is the desire to increase capital and make profit. We apply the principle of transitivity and find that the desire to make a profit leads to crises of overproduction and all the problems of people, which then happen at the stage of depression.

Of course, this is not proof of the failure of capitalism and not a call to abandon profit and capital. In the end, capitalism of our time is rather a “fork” of its original theoretical concept, since in its true form it does not work anywhere. Otherwise, there was no state ownership, customs restrictions, antitrust rules, government sanctions against commercial companies, etc. Barriers are not about capitalism. But where can we “tweak” things so that companies can operate quietly, delight us with new products, do not go bankrupt, do not lose their audience, and coexist peacefully?

The answer seems to me to be complex. The main block is the worldview of the Amazon founder. At least in words that are broadcast in the media, I like it. And in the first part of the block there will be a “Day 1” strategy. Companies must constantly evolve. Read the text of the novel in more detail:

In practice, this should at least manifest itself in the fact that they won’t suddenly take chargers out of boxes or block certain functions.

In the second part of the ideological block there should be that same focus on the client. But you don’t need to put all your chips on it. This will be difficult today, given the training of the audience by Jobs and Cook. But, in general, there are already established schemes. Custom design, for example. In other words, there is a standard smartphone, there is a flagship, and there are versions with wishes. Meizu once asked their fans to come up with a design for a new product. Take a look at what the projects from the participants in the competition for the design of the new flagship looked like:

Of course, you will have to develop some kind of standard chassis ten years in advance, but in the end you will be able to achieve subsequent ease of making changes to suit the wishes of the audience. Perhaps, who knows, even modularity can be added.

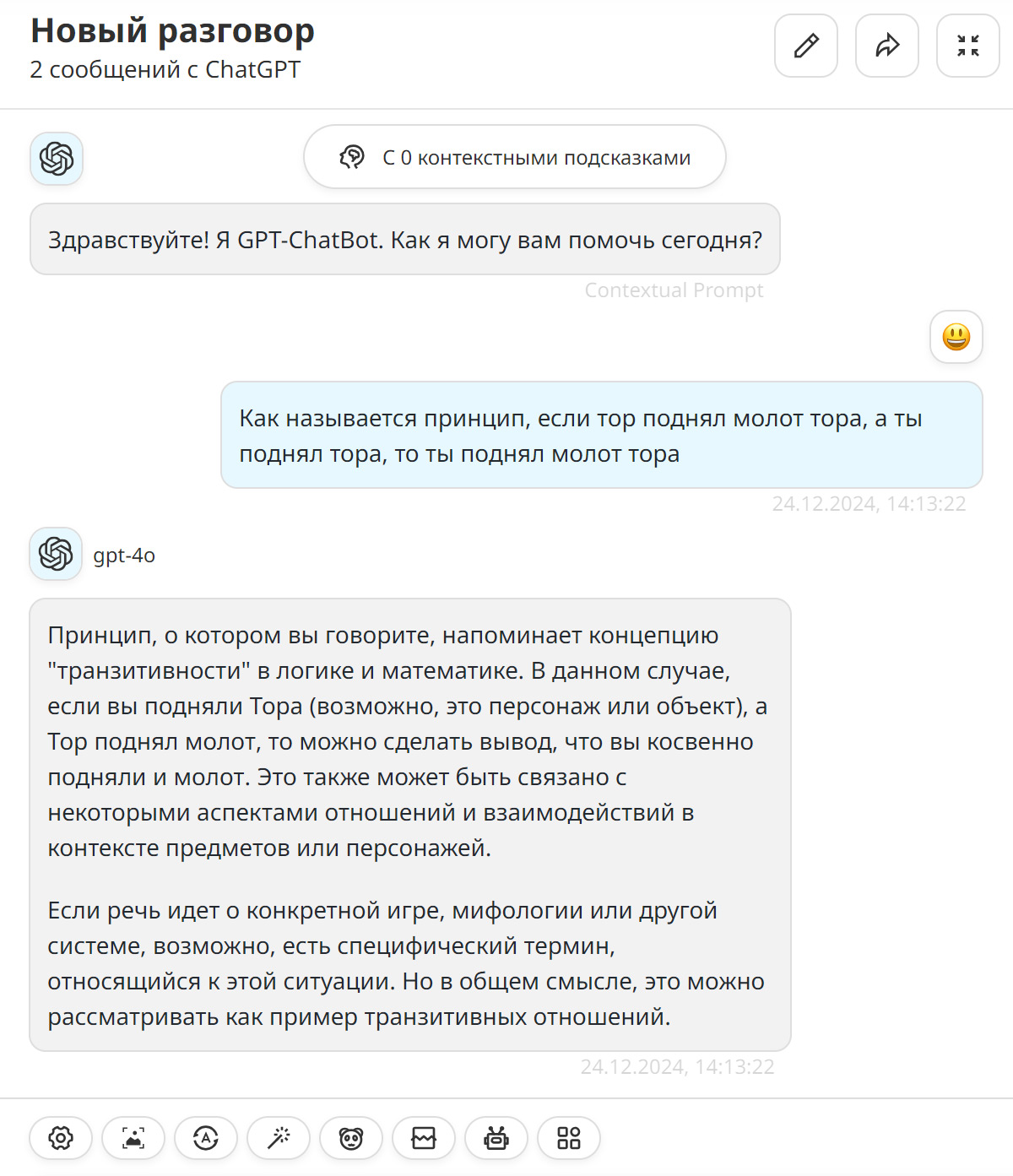

The rest of the answer should be intellectual property and royalties. But not in the form that exists today. Despite all the thoughtfulness, the schemes are too long. Ideally, there should be an automatic check of intellectual property against the three existing criteria, identifying the parent patent and forming a royalty agreement. In this case, the conditions also need to be assessed without human participation based on an algorithm based on an analysis of the degree of borrowing of the original idea. Unfortunately, today there are still situations where the patent holder deliberately does not issue licenses for his developments, depriving those wishing to produce them. Proving in court the critical importance for society of a technology patented by a competitor, which he refuses to sell in order to obtain a compulsory license, is a very slow matter. AI could probably help here. By the way, today I asked the neural network a question for the first time when I was trying to remember the principle of transitivity. Google search failed, but the chat bot easily solved my question.

What solutions would you offer to manufacturers so that there would be competition and no one would have to leave the market? Should companies reconsider profit margins with an even longer payback period in mind? Share in the comments. I am sure that among us there are professionals in economic theories who will be able to explain why the world has readily entered into every crisis for the last couple of centuries and has not tried to change the rules of the game.

Bold ideas, great inventions and successful products. Good luck!

Source: mobile-review.com