VEHICLE

When the computer screens in Houston suddenly stopped updating and displayed unreasonable values during the launch of Apollo 12, confusion erupted. What had happened? A young engineer saved the day.

READ MORE

The satellite boom – that’s how Sweden entered the space age

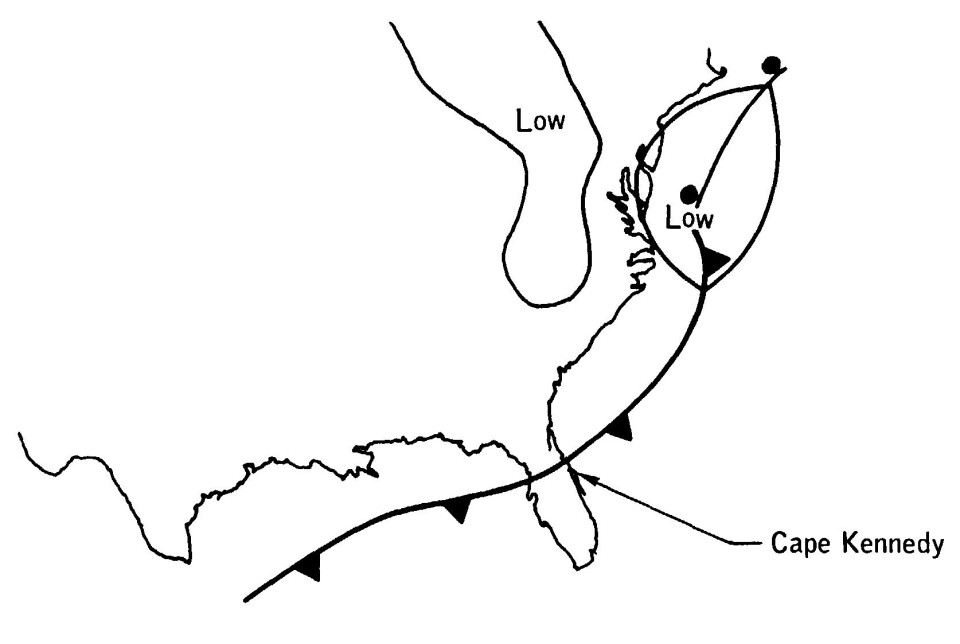

It is the morning of November 14, 1969. A cold front is passing through Florida, and it is rainy and windy. On ramp 39A at Cape Kennedy, Apollo 12 stands ready for immediate launch, with Commander Charles P “Pete” Conrad, Command Module Pilot Richard F “Dick” Gordon and Lunar Lander Pilot Alan L Bean lying on their backs, atop the Command Module.

Although it hasn’t thundered, like the day before, the dark sky still means that the top of the rocket is halfway towards the clouds even before it takes off.

10, 9, 8 … Lift-off!

145 miles away, in the control room in Houston, Texas, sits 25-year-old engineer John Aaron as Electrical, Environmental and Consumables Manager (EECOM). He is responsible for monitoring, among other things, the electrical system, cabin pressure and carbon dioxide. On his computer screens, he is currently monitoring the cabin pressure, to see that it drops as it should as the rocket ascends.

Three fuel cells were disconnected

36 seconds after the rocket has taken off, there is a big crackle on the radio. John Aaron’s screens stop updating, and when they come back a few seconds later, they also show completely unreasonable values. This also makes it impossible to debug. At the same time, in the command module, the astronauts’ instrument panel lights up like a Christmas tree.

No one in Houston knows that the rocket has just been struck by lightning, and that all three fuel cells on board have been disconnected.

After 52 seconds, the rocket is hit once more. This time the primary gyro platform is hit, and aboard the command module, Pete Conrad’s horizon instrument begins to spin. However, Dick Gordon’s instrument is fed from a backup system, and still works.

Fortunately, it is still the rocket’s own navigation system that controls the journey, while the command module’s system so far only presents its data to the astronauts.

READ MORE

Apollo 11 – a study in poorly controlled space quarantine

“Try setting SCE to AUX”

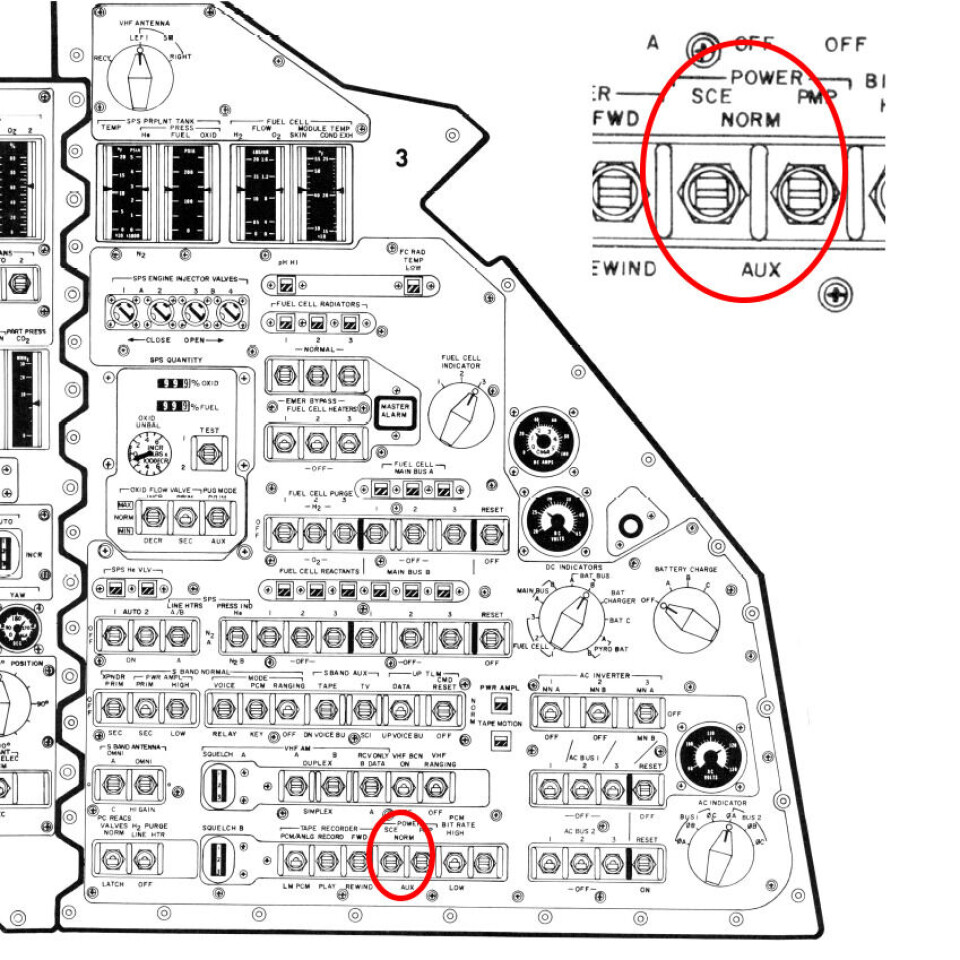

In the control room, John Aaron thinks he recognizes the pattern. He’s seen it before. That time, it was a unit on board, the Signal Conditioning Equipment (SCE), which during a test ran into trouble when the voltage temporarily dropped. He knows that it has two alternative modes for its power supply. Partly the normal one, which also protects and triggers in the event of disturbances, partly an extra one (auxiliary, AUX), which bypasses the protection circuits.

He exchanges a few words with a colleague to test his theory, and only hears the question the second time he gets it from air traffic controller Gerry Griffin.

– EECOM, what do you see?

Aaron replies:

– Try setting SCE to AUX.

Not many people know about the power switch and some confusion breaks out. But pilot Alan Bean has a clue, and once he resets it, the screens in Houston update normally again. When the telemetry now comes back, Aaron can see that the fuel cells have been disconnected, although he doesn’t yet know why. The crew reconnects them soon after.

Concern about parachutes

Some pressure and temperature sensors stopped working after the flash discharge, but they were fine without. However, it was not possible to know whether the parachute system had survived. Eventually, however, they landed on the moon, within walking distance of Surveyor III which had been launched a couple of years earlier.

Source: www.nyteknik.se