Hello.

Every day you produce information without realizing it. From the first moment I wake up, the phone understands that it is possible to turn on notifications and begins to vibrate quietly when they come to it. Against my will, I am involved in a constant process of creating data scattered throughout the world, and this process is opaque to me. Agree, it is difficult to realize that somewhere a schedule of your awakenings and going to bed is stored, and it is much more accurate than anything that you can remember not only in your life, but even in recent days. Human memory is not very accurate, but machines remember any detail. And this is data that is being accumulated somewhere in the depths of data centers scattered around the world.

I was thinking about the problem of how to calculate the amount of data I produce daily. Count the number of characters typed on the phone and computer, regard as data only text that has a conscious nature, remove all the template phrases “hello”, “how are you”, “wanted to ask” and the like? But this is exactly the same data that is stored in the depths of machines, and for the latter there is no difference between the banalities said in personal correspondence and the addresses of the pages that we typed during the day, but rather asked the search engine for certain things, that we were interested in.

How much data could a person create before the computer age? Question with an asterisk, because back then we didn’t have machines that could save our actions and thoughts. The transmission of information was analog in nature, the tablets may not have survived for centuries and turned into oral traditions, but they are an excellent example of the preservation and production of information, exactly the same as writing on birch bark or other information storage media. Exaggerating, we can say that the person himself is, to some extent, a carrier of information. Oral traditions passed down from generation to generation are also pure information. But it is machines that for the first time allow us to look at and evaluate the amount of data that we constantly produce. Just imagine how much data is generated in the world because of us. We will not touch on the philosophical aspect of the issue; here we can imagine that we create order from entropy, because any data is ordered and differs from the original sketchbook left after the Big Bang. My view of the matter is decidedly barbaric, the physical laws of the world, both known and not yet discovered, paint a picture of an order that we are simply not fully aware of.

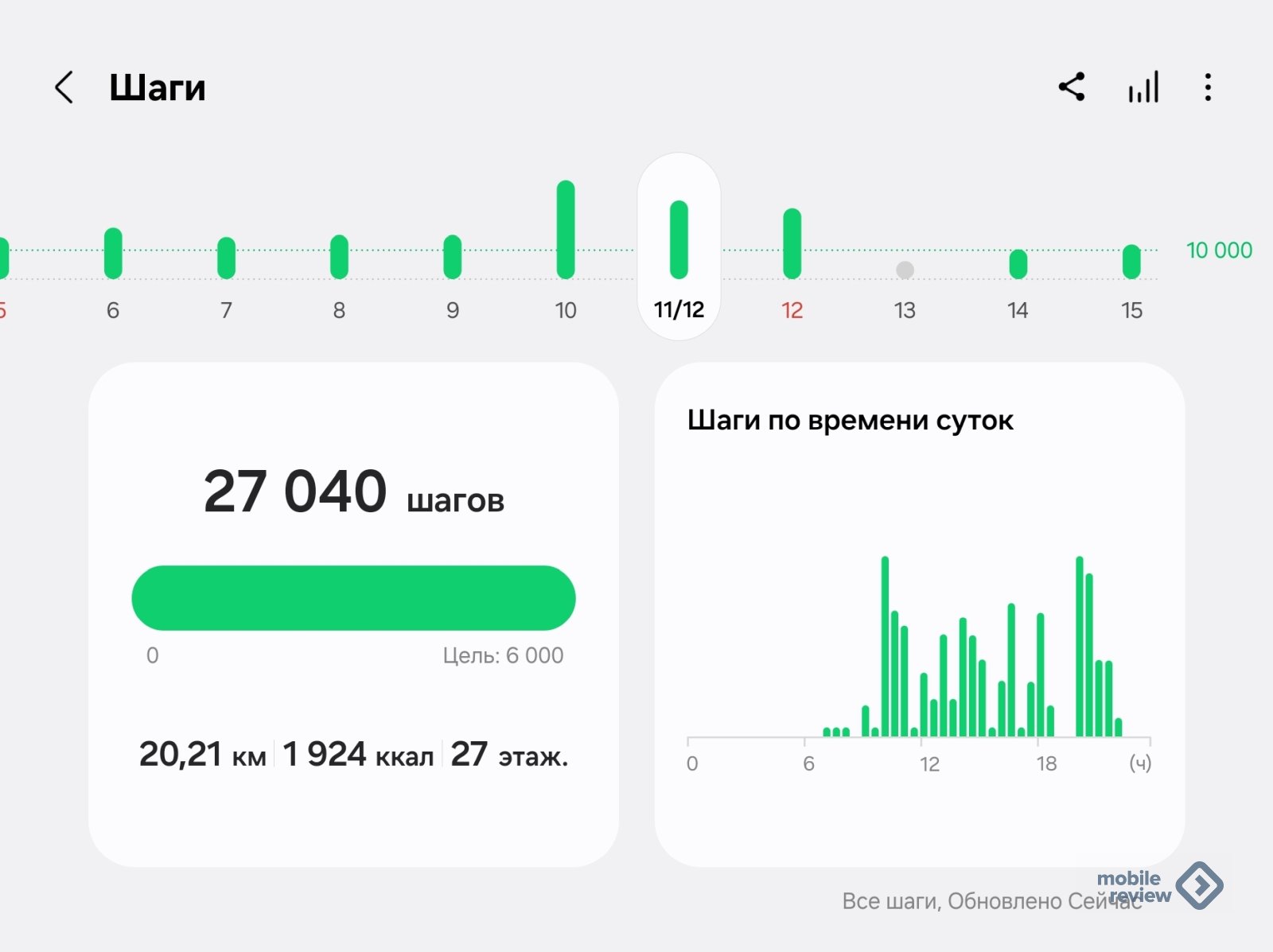

Conventionally, we can divide the data that we constantly create into conscious and unconscious, the former implying action on our part, an effort to create them and, to some extent, free will. The second arises because of our very existence, best described as data appearing because of our actions. We are walking somewhere down the street, surveillance cameras are filming us at this moment, the phone remembers preferences or counts how many steps we have walked. Not a single person in the past could say exactly where he was at such and such a time; his knowledge of his own life and memories were approximate.

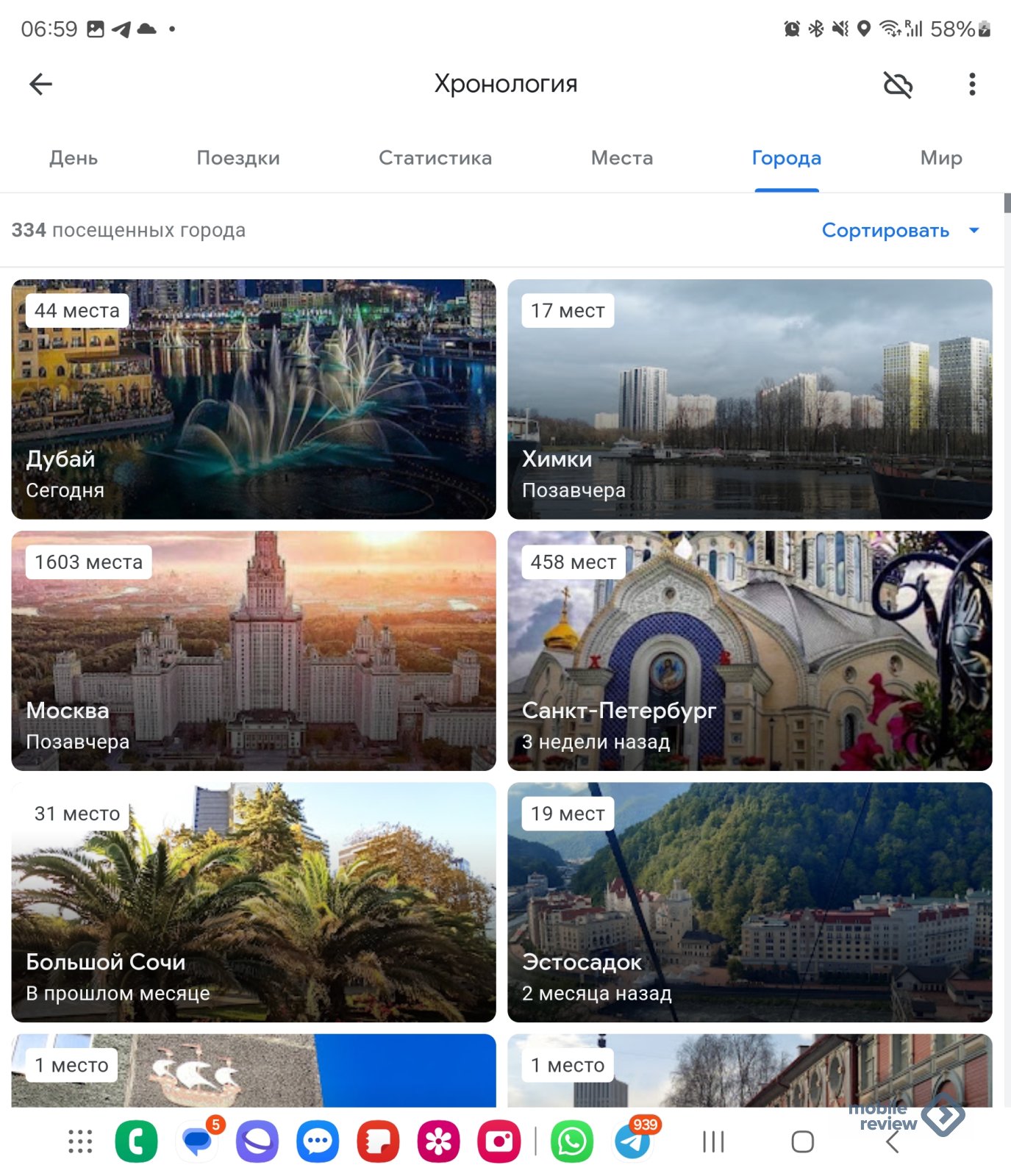

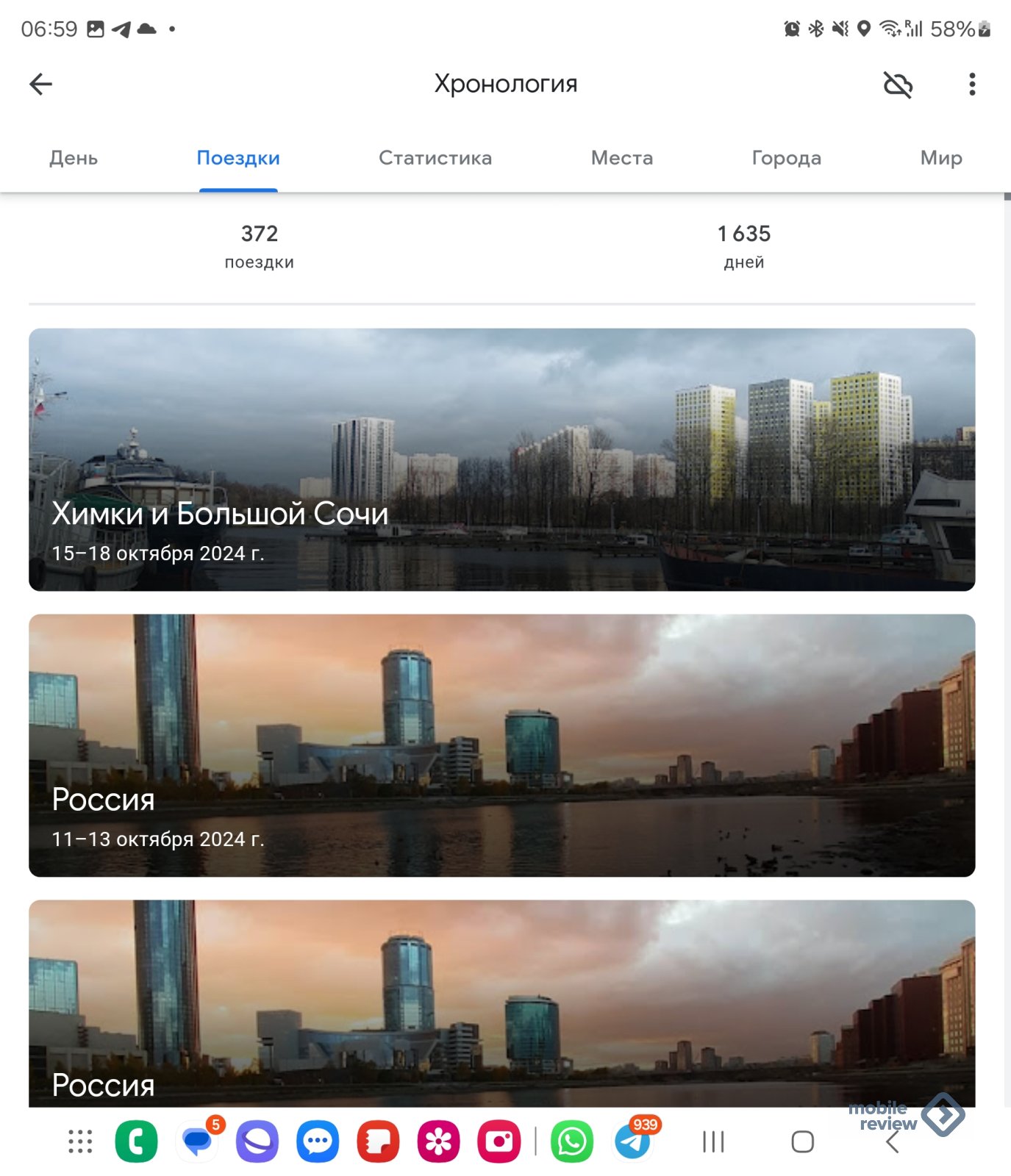

My life is rushing at a gallop, traveling and meeting all over the world, it is difficult for me to keep in mind everything that is happening around me. It is almost impossible to remember what happened in the recent past, the RAM of my biological brain periodically becomes full, new impressions displace old ones, and some cities become confusingly similar to others. The phone allows me to tell exactly where I was on such and such a date and what I was doing. The symbiosis of an external information carrier and one’s own memories provides a tool to restore the past in memory and do it accurately, quickly and without much energy expenditure. The sorting of memories is such that you can either restore the route of a particular day or look at some specific cities. There are more than enough tools for this, everyone uses the one that is familiar to them.

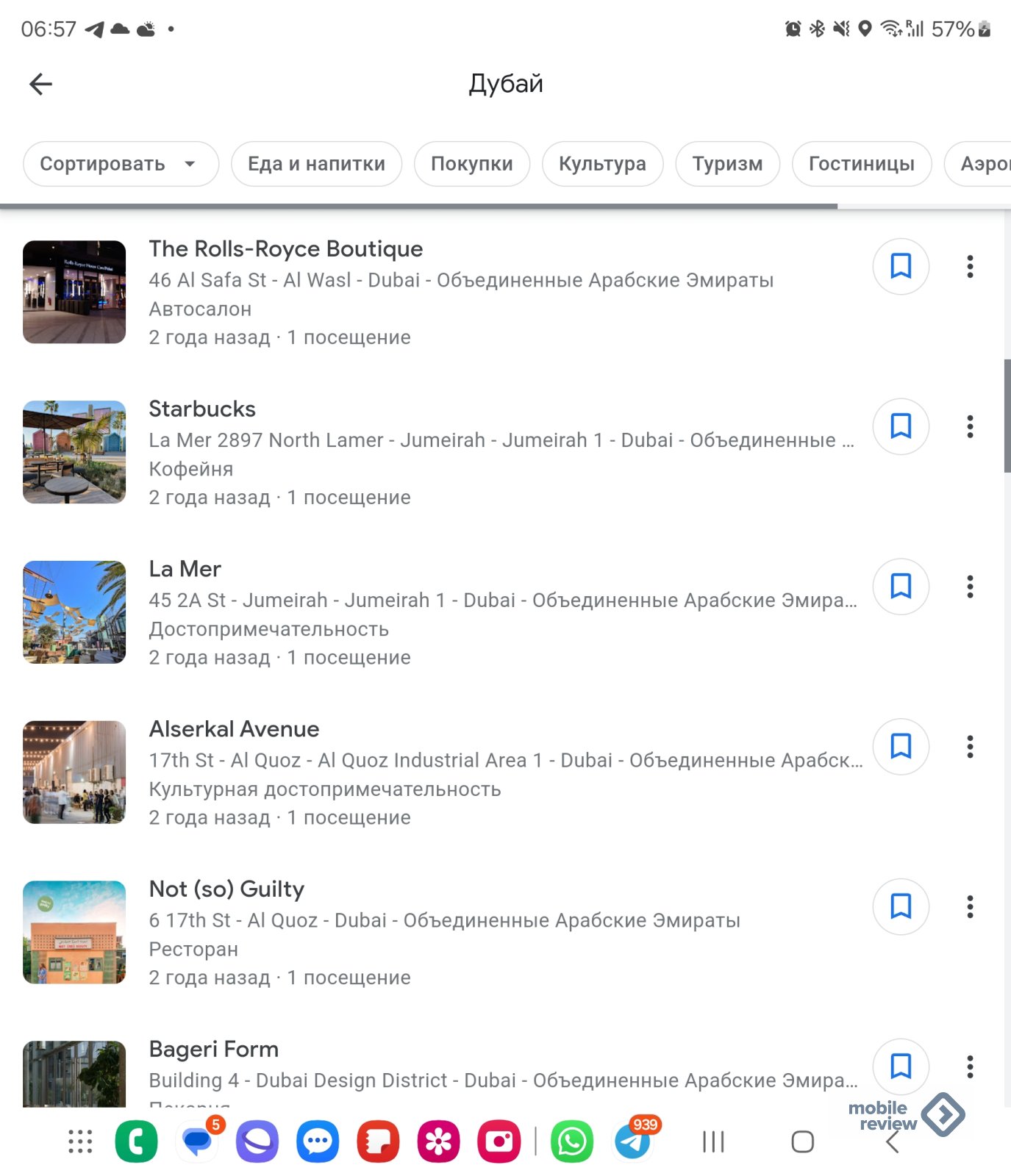

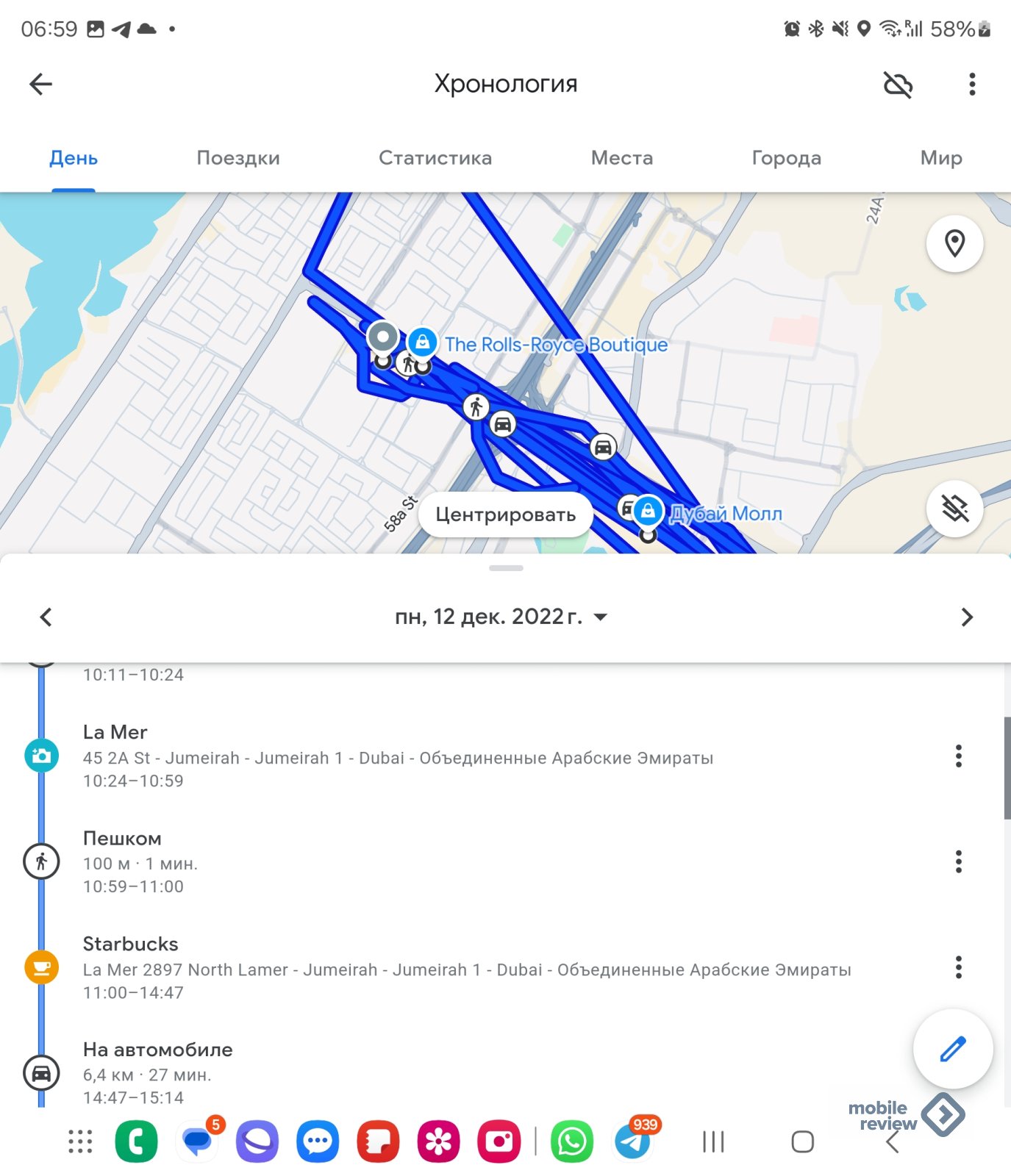

For example, in the chronology of Google maps you can see all your trips, remember the exact schedule of the day, rewind each day to the minute and see all the places visited. I looked at my movements on December 12, 2022 in Dubai.

Google’s tool is not the only one, it just shows in a convenient form the data that we create against our will. Our life is filled with data, we create them unconsciously and without much will; they exist simply by virtue of the very fact of our life.

I have been using smart watches for many years, they read different indicators. I don’t wonder why I need to know how many steps I walked ten years ago, but even this information is stored, as well as my heart rate, stress level and much more. Biographers of great people in the future will be able to access the data of deceased people in order to, delving into the readings of smart watches, restore their reactions recorded for specific dates and events, look for love affairs based on their changed pulse. I can imagine how you can dissect the past with such knowledge. If Cleopatra had worn a smart watch, we would have known down to the minute when the first meeting with Mark Antony took place and how worried she was and showed emotions.

People created diaries in which they carefully recorded their thoughts about events, places they visited and would like to remember. Unconscious accumulation of data does not require any action; there is no need for such diaries. You can “remember” most of your actions and what you once did with the help of a digital crutch. To remove such “memories”, you need to make an effort, which almost no one living today makes. But even if you take care of deleting this data, you will not destroy it in the company’s data centers, but simply block access to it for yourself. The data you produced will not go anywhere, it will still be stored somewhere, but you will lose it to yourself, nothing more. Corporate licensing agreements do not imply that the data you unconsciously create is your property; the data sets exist against your will, but provide a certain convenience.

Let me give you another example. Dubai has many different interesting places, as well as other huge cities that are centers of attraction. I stopped remembering the names of many restaurants and art galleries; only the most vivid impressions remain in my memory. I remember how an Iranian in the guise of a dervish danced in a huge gallery in Dubai, I remember about a year, but the name of the place slipped my mind. Why should I remember this for two years, especially since the place itself was not so striking. I wanted to get there and see what had changed there, what exhibitions were on. And I didn’t save anything specifically in order to find these galleries again.

I have almost a dozen different tools on my phone that allow me to restore the past. A minute later I found the name of the place, looked at the schedule of exhibitions and made plans for the next day. Do I like it? Definitely yes.

But what the classics described as a painful attempt to remember places, people, smells and emotions disappeared from my life. The phone has replaced my memory, and I rely on it a lot, I’m sure it won’t let me down. You can think about how you can instill memories in people by reformatting their digital traces, but about this somehow separately, not now.

The way we think and how much we rely on our memory has changed with the advent of digital media. Born in the USSR, I found analog phones, turned the dial to call my grandparents, and I perfectly remember their phone number, which has not existed for a long time. I remember exactly the same home numbers of all the places where I lived for a long time. Why I need this information today is unclear. But it was etched into my memory against my will; it is impossible to remove it from my memory arbitrarily. We remember a lot of things, but we almost never remember the numbers of those closest to us from memory, since we write them down in the phone book and do not dial the numbers. We don’t allow our brains to remember the same amounts of data as before. I don’t give any assessment of whether it’s good or not, it’s just become different.

Scientists say the way we remember data has changed. And this applies to literally every aspect of our daily lives, as we rely on our phones and change our behavior accordingly. I recently wrote about how the advent of GPS changed the profession of a taxi driver, as well as the way we navigate the terrain (to some extent we have become dumber, we are worse at coping with tasks that did not cause the slightest difficulty for our ancestors). But life has become simpler, safer, and it’s very relaxing. Now people would rather risk falling on their way to the subway than being devoured by some beast that jumps out from around the corner. Stress levels have dropped and life expectancy has increased dramatically compared to prehistoric times, when at twenty-five you were already considered an old man.

I tugged at the engineers I know who can see how much data the phone collects about me throughout the day. According to them, there are not many of them, on average 50-60 MB per person. The phone does not record the content of conversations or correspondence, but the very facts that they took place. Hence the small amount of data, but this is what can be called unconscious accumulation, something that happens without our will. This kind of data is important and useful, and it changes the way we live in the world. But the main thing is the conscious accumulation of data, when we remember many things and form our worldview through the tools given to us by the digital world.

It would be correct to separate the discussion of conscious data storage and the unconscious, but for now I invite you to think and answer simple questions for yourself:

- How much data do you create against your will every day?

- Can you opt out of creating such data?

- How much conscious data do you have and what kind of data is it?

Try to think about these questions. Just think, and not pick up the phone, copy what you wrote and ask the search engine for an answer. After all, search is another tool of the modern world, when it seems that the answers to all questions already exist and there is no need to think, but just type a question and get an answer. Just like there are no attempts to remember something forgotten and get pleasure from the fact that you managed to get it from the shelves of your own memory. We have almost no more thoughts when we force our brains to turn on and think, solve problems from the real world. And this also characterizes our ideal instrument, which can remember for us, give answers to any questions, and most importantly, “thinks” for us.

In a separate article we will talk about what memories and how we save consciously, as well as what we do with them later.

Source: mobile-review.com