Ocean water is intruding kilometers beneath the “Apocalypse Glacier” in Antarctica, making it more vulnerable to melting than previously thought, according to new research that used radar data from space to make an X-ray of the critical glacier.

| EPA/NASA/OIB/Jeremy Harbeck

As the salty, relatively warm ocean water meets the ice, it causes “heavy melting” beneath the glacier and could mean that predictions of global sea-level rise are being underestimated, according to the study published Monday (20 /5) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Advertising

West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier – nicknamed the ‘Apocalypse Glacier’ because its collapse could cause catastrophic sea-level rise – is the world’s widest glacier at 192,000 square kilometers (about the size of Britain or the of Florida in the USA). It is also Antarctica’s most vulnerable and unstable glacier, in large part because the ground it sits on slopes downward, allowing ocean waters to eat away at its ice.

Thwaites, which already contributes 4% to global sea level rise, has enough ice to raise sea levels by more than 60cm. But because it also acts as a natural barrier to the surrounding ice in West Antarctica, scientists have estimated that its complete collapse could eventually lead to a sea level rise of around 3 meters – which would be devastating for its coastal communities world.

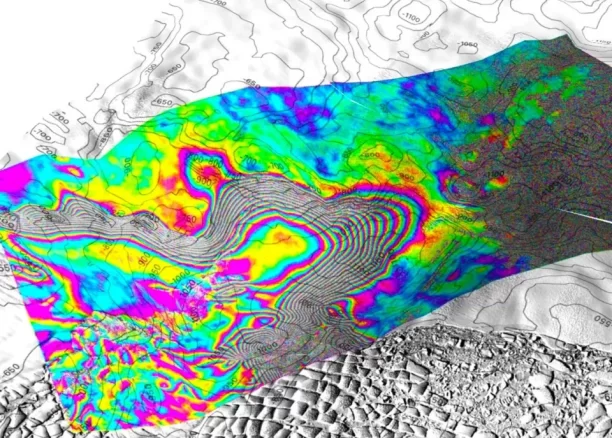

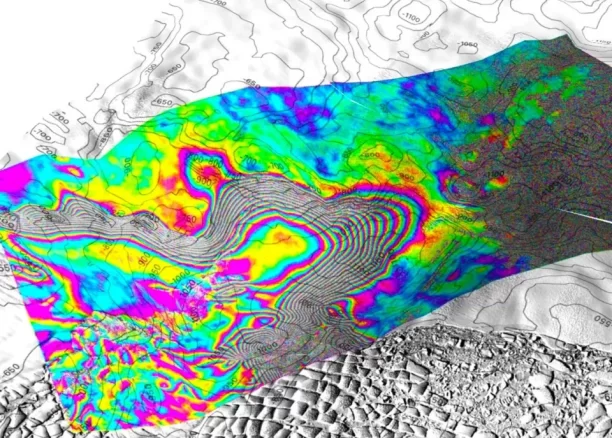

Radiography via satellite

A team of glaciologists – led by scientists from the University of California, Irvine – used high-resolution satellite radar data collected between March and June last year to create an X-ray of the glacier. This allowed them to create a picture of changes at the Thwaites grounding line, the point where the glacier emerges from the sea floor and turns into a floating ice shelf. Ground lines are vital to the stability of the glaciers and a key point of vulnerability for Thwaites, but they are difficult to study.

Advertising

| Eric Rignot/UC Irvine

The scientists observed seawater intruding under the glacier for many kilometers and then retreating again, following the daily rhythm of the tides. When the water flows in, it’s enough to “lift” the surface of the glacier by centimeters, Eric Rignot, professor of Earth systems science at the University of California, Irvine and co-author of the study, told CNNi.

Melting the ice

The speed of seawater, which moves significant distances in a short period of time, increases the melting of glaciers because once the ice melts, fresh water is swept away and replaced by warmer seawater, Rignot said.

“This process of widespread, massive seawater intrusion will increase the projected sea level rise from Antarctica,” he added.

With information from cnn.gr

Source: enallaktikidrasi.com