How are modern humans unique in evolutionary history?

A team of researchers discovered that a Neanderthal with Down syndrome survived to the age of six thanks to the care of his own community.

Living in societies and caring for others is probably what has allowed our species to not only survive, but to evolve over billions of years.

That’s a widely held theory among scientists, supported by new evidence from a study of a small bone with unusual features.

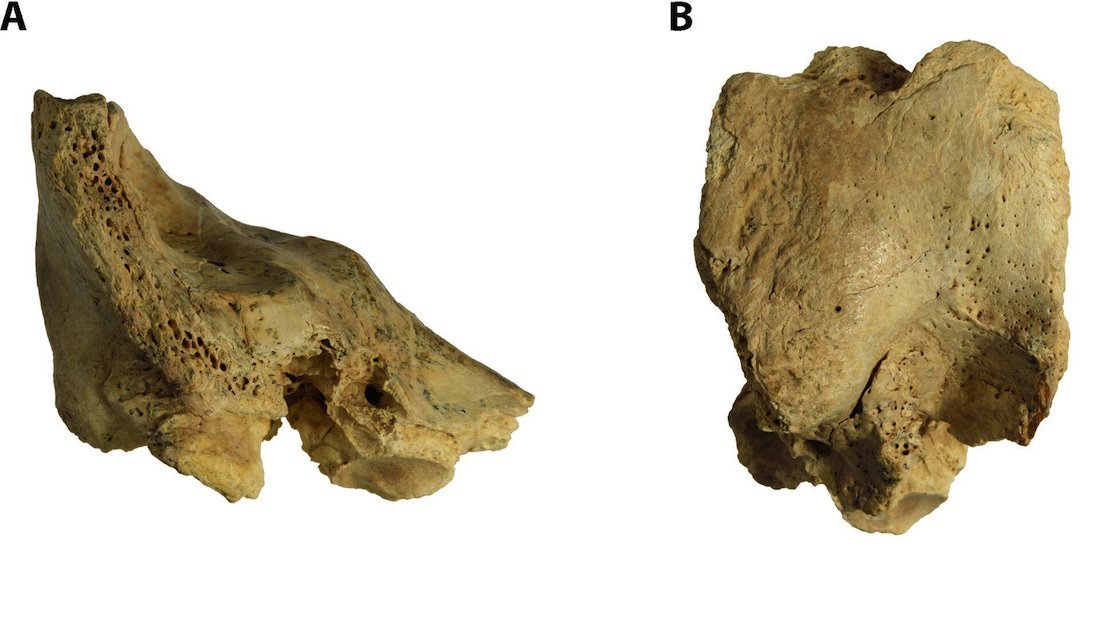

In 1989, a team of paleontologists discovered a five-centimeter-long bone fragment – part of the inner ear of a six-year-old Neanderthal from the Cova Negra cave near the Spanish city of Valencia.

Although they could not determine whether the bone belonged to a male or female child, the team named the Neanderthal Tina.

Finding such a small bone, such as a Neanderthal ear canal fragment, does not happen often.

Archaeologists usually find only larger remains such as skulls, teeth or limb bones.

At the time, researchers were more interested in other remains from the excavation, but they were aware that this was a valuable discovery.

Neanderthals inhabited Europe for hundreds of thousands of years until they became extinct 40,000 years ago.

They are one of our closest known relatives.

Homo sapiens (modern humans) and Neanderthals (Homo neandertalensis) are classified as different types of hominids, which lived at the same time and descended from a common ancestor.

This fossil is estimated to date from the Upper Pleistocene period, which means it is between 120,000 and 40,000 years old.

“The real surprise came with the computed tomography scan, which showed that the Neanderthal had birth defects consistent with Down’s syndrome and which would have caused significant health problems throughout her life,” says Professor Emeritus Valentin Villaverde Bonilla, from the Department of Prehistory at the University in Valencia, who led a team of researchers.

BBC is in Serbian from now on and on YouTube, follow us HERE.

What have scientists discovered about Tina?

Villaverde says the damage found in the fossil indicates that Tina suffered from constant ear infections, deafness, balance problems and possibly impaired movement.

“She was facing significant difficulties that threatened her survival. Obstacles that would have been impossible to overcome if she had to do it alone,” he says.

Down syndrome is a genetic condition in which a person has an extra chromosome that can cause various degrees of intellectual disability, as well as problems with the heart, digestion and other organs.

Then again, Tina lived to be six years old, which far exceeds the normal life expectancy of children with Down syndrome in prehistoric populations.

By comparison, at the beginning of the 20th century, between the twenties and forties, the survival rate for children with Down syndrome was between nine and 12 years.

The team from the University of Alcala, which received Tina’s small ear bone for analysis, concluded that the care necessary for the child’s survival over a period of several years probably exceeded the capabilities of the mother alone and required the help of other members of the social group.

Their findings were published in the July edition of the journal Sajens advansiz.

A key question facing scientists is whether this concern was altruistic—a behavior of great adaptive value—or out of self-interest.

After all, Neanderthals were hunter-gatherer groups that moved across very wide territories.

“If they didn’t pay special attention to this child, he wouldn’t have lived to the age of six,” says Villaverde.

What does the behavior of Neanderthals say about evolution

Neanderthals have long been known to care for others with disabilities, but the motivation behind this is debated.

“Some authors believe that caring took place between individuals capable of reciprocating, while others argue that caring arose out of compassion coupled with other highly adaptive social behaviors,” the study authors say.

Mercedes Conde Valverde, researcher from the Chair of Evolutionary Otoacoustics and Paleoanthropology at HM Hospitals and the University of Alcala, spoke to BBC Mundo from Atapuerca, an archaeological site in northern Spain.

She led the Spanish researchers in charge of analyzing Tina’s small bone.

“There are remains of Neanderthals with pathologies (diseases and injuries) that probably required the help of the group.

“But they were all adults and it was discovered that they had pathologies that they were not born with, but acquired during their lives: wounds, diseases, broken bones and other injuries,” she says.

“The debate surrounding this behavior is whether, when you’re an adult, group helping is really an altruistic behavior – I’m helping you because I feel that way – or is it a mutual aid behavior – I’m helping you because you’ve helped me in the past or because you will help me in the future.”

How altruistic are we?

Tina’s case is exceptional because she is a child who was born with these problems and yet lived for at least six years.

“That means they had to help her a lot and take care of her, but since she was a child, they probably didn’t expect her to reciprocate,” says the researcher.

The study on children with serious pathologies is particularly interesting, since children have a very limited possibility of reciprocating help.

This tells us about the evolution of our species that Neanderthals really possessed altruistic behavior, in the same way that we possess it.

There is a famous case of a chimpanzee with Down syndrome who lived for 23 months thanks to the care of his mother, who was assisted by her eldest daughter.

When the daughter stopped helping the mother care for her own offspring, the mother could no longer provide the necessary care and the offspring died.

The researchers say that if both Neanderthals and modern humans possess compassion and come from two different evolutionary lineages, “this means that at least the common ancestor already possessed it and that’s why both lineages inherited it,” says Conde Valverde.

The human species that gave birth to Neanderthals and Homo sapiens lived a million years ago.

“We suggest that other members of the community may have helped the girl directly or helped the mother, relieving her of tasks so she could care for Tina.

“Neanderthals were a species that was very similar to us,” she says.

The expression of care among Neanderthals is part of a wider and more complex social context.

By studying children, researchers have the opportunity to ascertain whether caring is directly related to a complex social strategy such as collaborative parenting.

“On the one hand, some authors argue that it is not possible to draw a firm conclusion about care based on mere paleopathological evidence and that conclusions are drawn based on unproven assumptions.

“In recent years, however, the idea that paleopathological evidence is a source of information about the existence of care in prehistoric times has gained momentum,” the study says.

Another particularly interesting aspect of this field of care bioarchaeology dealing with hominid fossils is determining why people devoted part of their time and effort to caring for a member of their own group with a temporary or permanent disability.

This discovery “seems wonderful to me because it puts people with Down syndrome in the spotlight. We are all part of human evolution, we all have a reference and we can all represent ourselves.

“We’ve always been there, we’ve always traveled together,” says Ignacio Martinez Mendizabal, co-director of the Presidency of Otoacoustic Research and Paleoanthropology at the University of Alcala.

“And then there is a more technical, deeper scientific question of an evolutionary-biological problem, which is the question of when and how this very human behavior – because it is truly unique to humans – of caring for the vulnerable within the community first appeared.

“I truly believe that there is no other team in the world at this moment that could, with this fossil, understand what he had and, above all, carry out all the research and manage to publish it in a journal like Science Advances.” concludes the professor.

Watch the video: This is what a Neanderthal looked like

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube i To Viber. If you have a topic proposal for us, contact us at bbcnasrpskom@bbc.co.uk

News

Source: www.vijesti.me